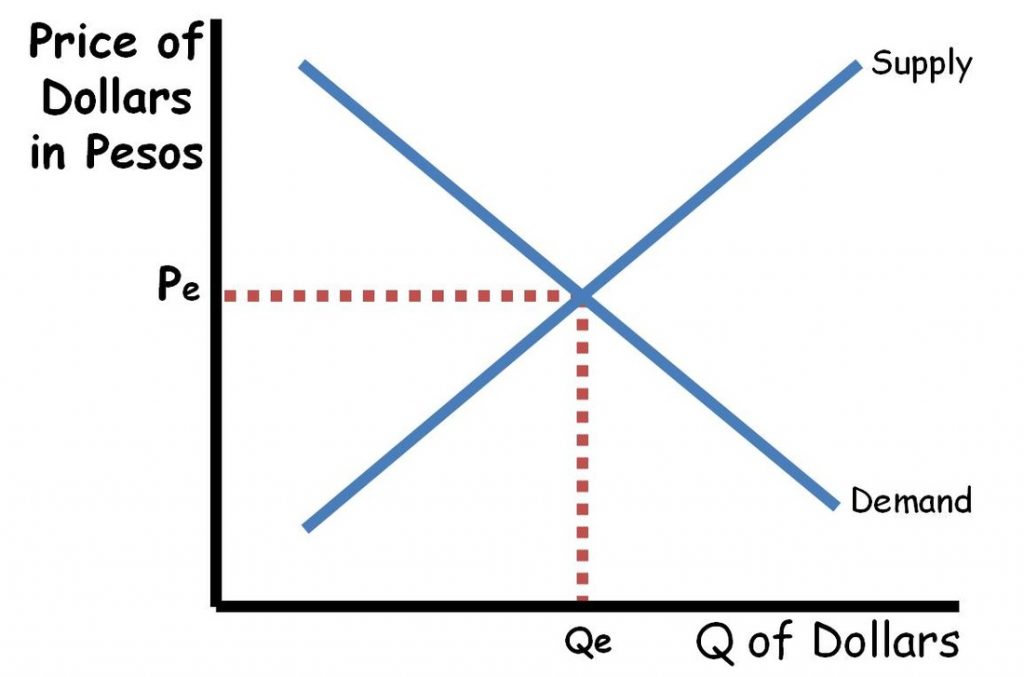

For example, at an interest rate of 21%, the quantity of funds supplied increases to $750 billion, while the quantity demanded decreases to $480 billion. If the interest rate (remember, this measures the “price” in the financial market) is above the equilibrium level, then an excess supply, or a surplus, of financial capital will arise in this market. The equilibrium occurs at an interest rate of 15%, where the quantity of funds demanded and the quantity supplied are equal at an equilibrium quantity of $600 billion. In the financial market for credit cards in Figure 4.5, the supply curve (S) and the demand curve (D) cross at the equilibrium point (E). Conversely, if the interest rate on credit cards falls, the quantity of financial capital supplied in the credit card market will decrease and the quantity demanded will increase. Consequently, as the interest rate paid on credit card borrowing rises, more firms will be eager to issue credit cards and to encourage customers to use them. According to the law of supply, a higher price increases the quantity supplied. As the interest rate rises, consumers will reduce the quantity that they borrow. According to the law of demand, a higher rate of return (that is, a higher price) will decrease the quantity demanded. The laws of demand and supply continue to apply in the financial markets. Table 4.5 Demand and Supply for Borrowing Money with Credit Cards Table 4.5 shows the quantity of financial capital that consumers demand at various interest rates and the quantity that credit card firms (often banks) are willing to supply. The vertical or price axis shows the rate of return, which in the case of credit card borrowing we can measure with an interest rate. The horizontal axis of the financial market shows the quantity of money loaned or borrowed in this market. Thus, Americans pay tens of billions of dollars every year in interest on their credit cards-plus basic fees for the credit card or fees for late payments.įigure 4.5 illustrates demand and supply in the financial market for credit cards. Let’s say that, on average, the annual interest rate for credit card borrowing is 15% per year. As of 2021, just over 45% of American families carried some credit card debt. In May 2021, Americans had about $807 billion outstanding in credit card debts. A typical credit card interest rate ranges from 12% to 18% per year.

Money market graph plus#

Credit cards allow you to borrow money from the card's issuer, and pay back the borrowed amount plus interest, although most allow you a period of time in which you can repay the loan without paying interest. In 2021, almost 200 million Americans were cardholders. Let’s consider the market for borrowing money with credit cards. Similarly, if you demand a loan to buy a car or a computer, you will need to pay interest on the money you borrow. The interest the bank pays you as a percent of your deposits is the interest rate. For example, when you supply money into a savings account at a bank, you receive interest on your deposit.

The simplest example of a rate of return is the interest rate. This rate of return can come in a variety of forms, depending on the type of investment. In financial markets, those who supply financial capital through saving expect to receive a rate of return, while those who demand financial capital by receiving funds expect to pay a rate of return. In any market, the price is what suppliers receive and what demanders pay. Who Demands and Who Supplies in Financial Markets? For a more detailed treatment of the different kinds of financial investments like bank accounts, stocks and bonds, see the Financial Markets chapter. Those who borrow money are on the demand side of the financial market. Those who save money (or make financial investments, which is the same thing), whether individuals or businesses, are on the supply side of the financial market. In this section, we will determine how the demand and supply model links those who wish to supply financial capital (i.e., savings) with those who demand financial capital (i.e., borrowing). Some firms reinvested their savings in their own businesses. Some was invested in private companies or loaned to government agencies that wanted to borrow money to raise funds for purposes like building roads or mass transit. Where did that savings go and how was it used? Some of the savings ended up in banks, which in turn loaned the money to individuals or businesses that wanted to borrow money. United States' households, institutions, and domestic businesses saved almost $1.3 trillion in 2015.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)